The idea of iterations applies to problem solving in general.

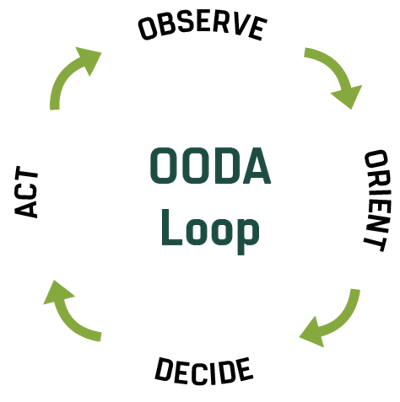

If you don’t trust us, take it from the United States Air Force. Developed originally by combat pilot and military theorist, Colonel John Boyd, the “OODA Loop” is an excellent methodology for working through dynamic challenges. OODA stands for Observe-Orient-Decide-Act.

Boyd called it a loop because we are never really done. Once we have gotten to “act” stage, all our premises and constraints have changed. Now we must go back to the beginning to observe our new position and begin the loop once more.

The goal is to move through the OODA loop repeatedly, faster than everyone else around you.

The path to rapid product development is paved with as many quick and dirty prototype iterations as possible. In the early stages of a project, all new concepts should be proven in the quickest and most inexpensive way possible. We refer to this idea as the minimum viable product (MVP).

Here is how we execute the OODA loop in rapid product development.

For Rapid Product Development, Observe the Problem

This is an example of a common mistake we see:

The end user, client, or colleague tells the new product development team what the problem is. The designers do their job, solving that problem. The hitch is that the designer did not know that the solution would be used in a wash-down environment. While the new product worked flawlessly in the lab, it will never hold up in the field.

Observation is key in rapid product development. Ask many questions, even more than you think. Watch the problem in action. If you can, try to live the problem repeatedly until it is your problem. Only then will you have the ability to fully comprehend the challenge and rise above it.

Orient yourself in rapid product development

This can often be the hardest part of the loop. Sometimes our observations show us things so far from what we expected we literally cannot comprehend them. From the first observation in rapid product development, we must let go of preconceived notions and focus on what we have witnessed and learned.

Here is a good example if you can remember what a VHS Tape is:

Imagine if you worked for an electronics manufacturer. The current problem is that VHS tapes take too long to rewind. You spend the next six months testing all kinds of faster motors, and ways to sense the end of the tape to prevent breaks at such high speeds.

Meanwhile, your competitor is developing a DVD player. These have higher video quality, and they do not even need to be rewound. VHS has been the standard for longer than you can remember. Everyone owns a VHS player, no one owns a DVD player. It is impossible to comprehend that a video tape player with high-speed rewinding is not the solution to rewinding VHS tapes faster.

In your observation phase you noted the DVD player’s ability to “rewind” instantaneously. When orienting yourself, you must except this truth and save your business the heartache of developing a great product that nobody needs.

Decide next steps in rapid product development

Now that you have oriented yourself, the next step in the rapid product development cycle is to determine what to do about it. Often, we are faced with many different paths forward, each with distinct pros and cons.

The objective is to cycle the OODA Loop as many times as possible in the shortest amount of time. It is easy to get mired in deciding the next step.

Don’t.

Do not worry about solving the whole problem right away. Test each premise on its own. If you have five different paths forward, either of your top two are probably fine. Now figure out how to run those paths through the OODA loop as quickly as possible.

Act on your decisions for rapid product development

This is where we make a prototype. In rapid product development we tend only to consider the building stage, disregarding the importance of observation. As we have learned, this is only one step in the process. Building prototypes quickly that do not move us towards our goal of solving the problem are not helpful.

We do want to move quickly. Always ask yourself:

Am I taking the quickest path to test my idea?

Early on we are not interested in solving the whole problem, only testing concepts that lead us to our solution. Say for example your problem is that your car is cold in the morning:

We are quite certain that we want a remote which can turn on the heated seats, put the air on high heat, and defrost the windshield. Our first “prototype” would be to walk outside and turn on the heated seats, warm air, and windshield defrost. We learn, that without first turning on the car, the other systems are useless. Had we developed a remote with these functions, but which could not start the car, we would have to start the design over. In this case we learned in the first five minutes that the vehicle must be running in order to warm up. Now we can begin the loop again this time with more knowledge of our solution.

Observe again: Start the OODA Loop all over

With every prototype iteration we build, we will have the opportunity to learn something new. Our whole frame of reference has changed. It is important to carefully observe and truly re-orient before moving on to another test.

Rapid product development is so much more than just building prototypes. When engaging in your next project, try the OODA Loop and remember that the goal is to iterate and re-orient as quickly as possible.